ONLINE EXHIBITION OF THE PAINTING DEPARTMENT MASTER STUDY PROGRAMME STUDENTS

The irreconcilable diversity evident in the show’s eight participants and their works testifies to contemporary and conceptual transformations underway at the Painting department of the Art Academy of Latvia. These transformations are most likely but a symptom of larger processes of change in and outside art. However, the necessity of visual representation seems unavoidable for as long as it makes sense to bestow the name of painting to the genre. It is unavoidable for as long as we consider a conversation between an artist, an individual viewer, an expert and the public to be a necessity. For the young artists of the Art Academy of Latvia, this representation has been missing, in its classical or at least customary form, but it doesn’t mean that its necessity has dwindled. This partially virtual hybrid exhibition is an attempt to maintain the conversation at a time of crisis, at the same time testifying to the processes fermenting at the Painting department of the Academy.

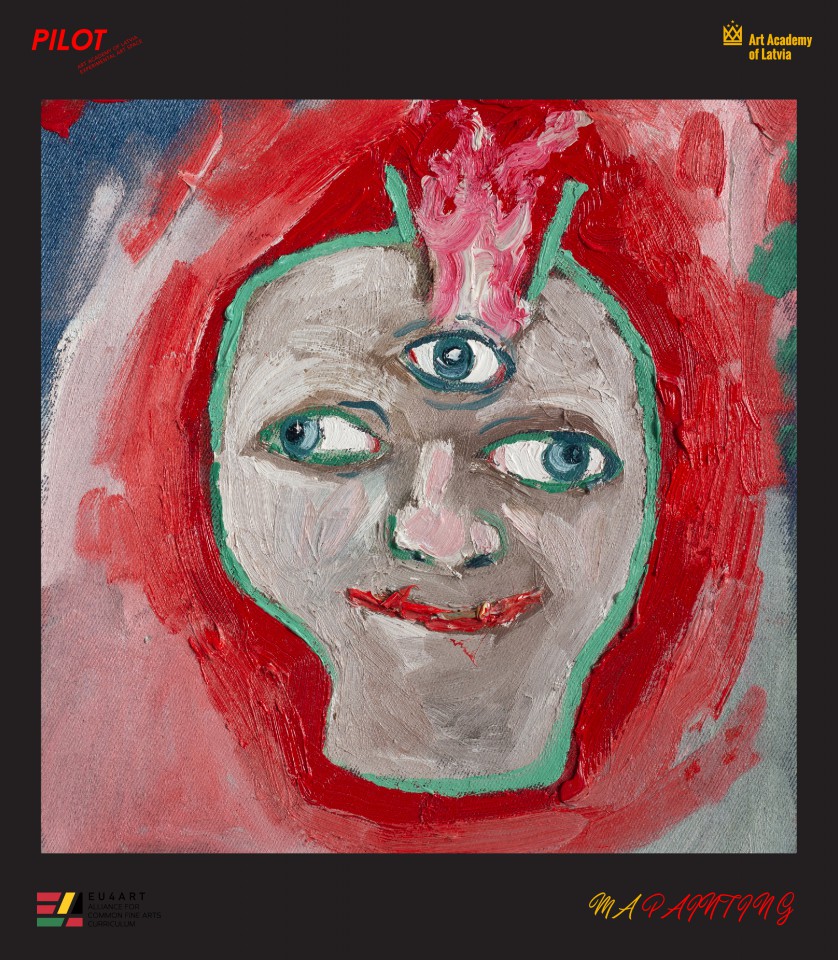

Envija Medne

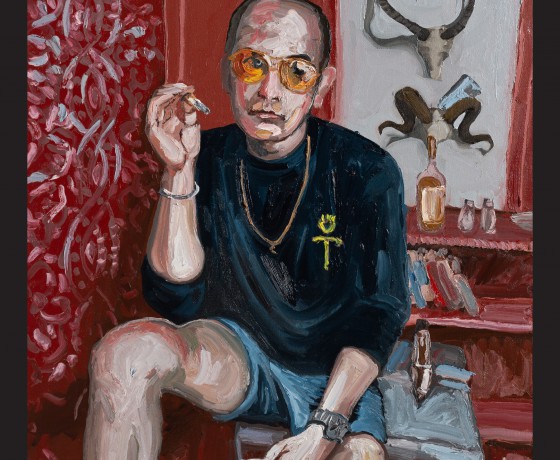

‘Name one thing that troubles you the most and one that helps you the most in the way the Painting department at the Art Academy of Latvia is organized and functions.’ Envija Medne (1990) can give the same answer to both questions: that the department lets you do whatever you want. For as long as she can remember herself, Medne has always wanted to paint. (‘I think I was born like this.’) She pondered going to Roži, the Janis Rozentāls Art School, for high school, but chose the Rīga Art and Design Secondary School instead, honoring family tradition. She was never one for ready-made landscape and nature painting exercises and felt she should veer into a more creative direction. But for a long time she lacked a teacher or a guide, therefore for years – even after starting undergraduate studies at the Art Academy of Latvia – she struggled with a lack of self-confidence and lack of faith in herself. It all changed during an Erasmus exchange in Gdansk, where ‘a new world came into being’ for her. Afterwards, she became acquainted with teachers who understood her, including former professor Andris Eglītis and her BA supervisor Miķelis Fišers.

Medne has conceptualized her MA thesis as a book of study and advice for her former, creatively unsure self, which would maybe turn out to be of use to others on a similar path. Meanwhile in the rich array of Medne’s works for the show we can observe her enthusiasm for big figural compositions and formal affairs, as well as her fascination with portraits of vivid and contradictory persons. We find Johnny Depp and Hunter Thompson, as well as former Health Minister Ilze Viņķele, who was, for a time, ‘the leading woman in Latvia’. Meanwhile the painting with the cosmos bursting into a human head through a suddenly open channel could turn out to be the painter herself and, if we’re being honest, anyone of us.

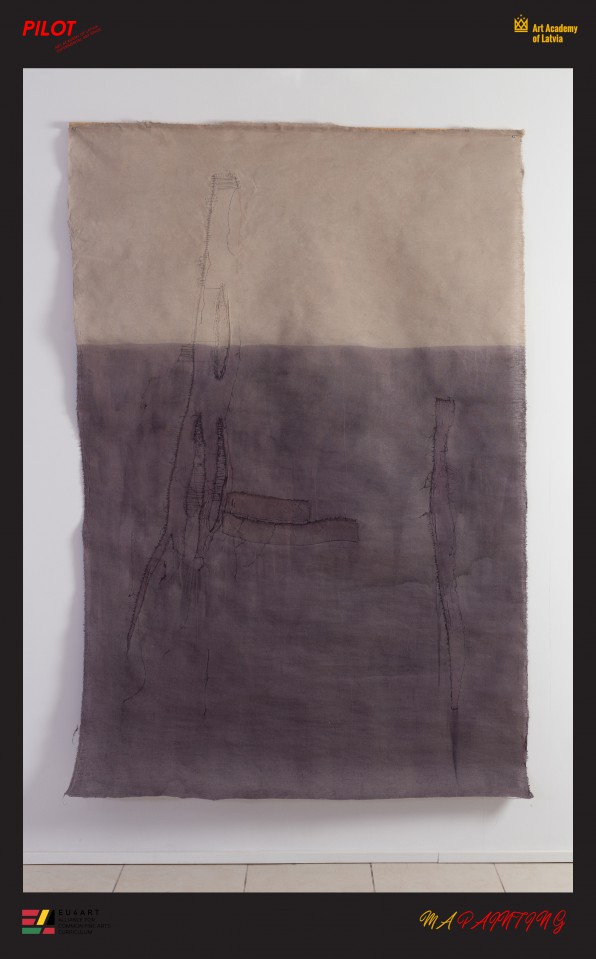

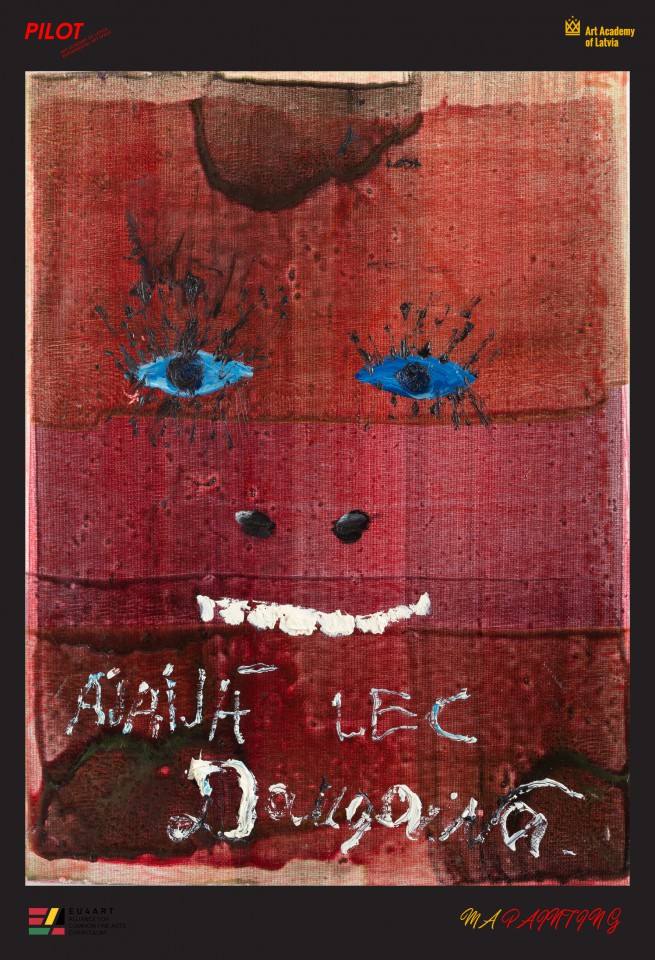

Konstance Zariņa

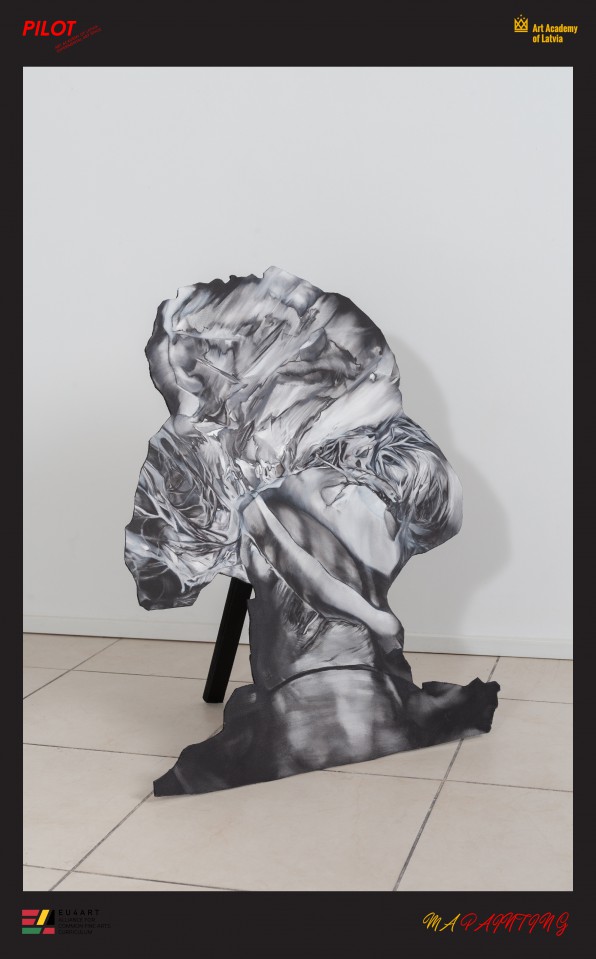

Konstance Zariņa’s (1988) presence at the Painting department of the Art Academy of Latvia is somewhat contradictory, as she doesn’t shy away from admitting she doesn’t really believe in painting or art anymore. Nevertheless, in cooperation with her MA supervisor Kristaps Ancāns, she is trying to scrutinize and examine the traditional structures and conventions of painting, and in the end rejecting or affirming them through exaggerated forms. According to Zariņa, most artists do superfluous things that could easily be excluded from the definition of the genre. In her works, for example, in the projection of a personal photo painted on a linen cloth she weaved herself, Zariņa tries to stick to the facts as much as possible, dropping an ‘anchor in reality’, with which she can at least try to put the viewer into a position she herself had been in.

Zariņa graduated with a bachelor’s degree as early as 2013 and took a breather before returning to pursue a master’s degree. During this pause she found answers to her most important personal questions, meaning she isn’t looking for anything anymore. Except, perhaps, for the answer to the question whether it’s still possible to say something new in art. Fortunately or not, the department grants enough freedom for such ventures.

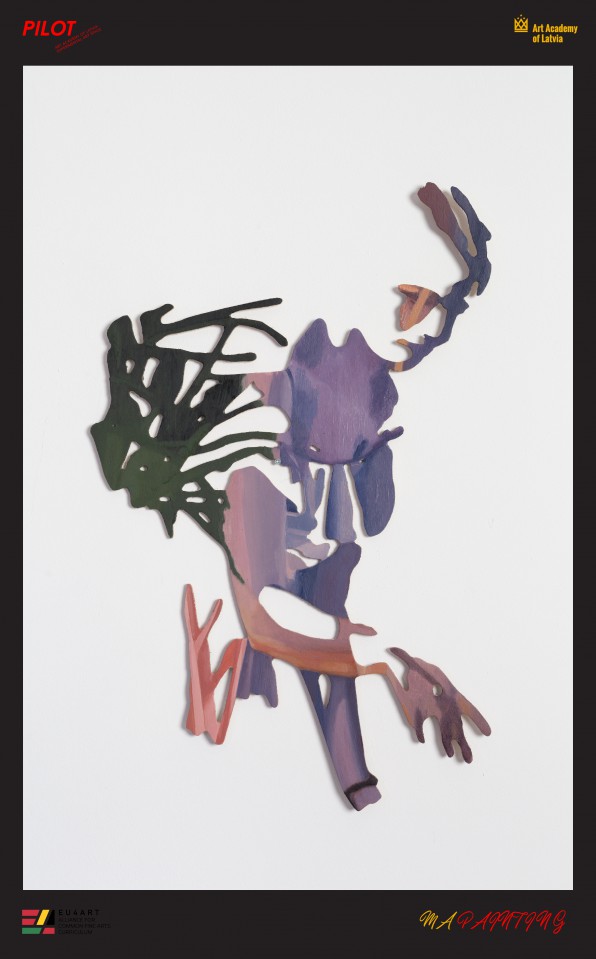

Kristīne Daukšte

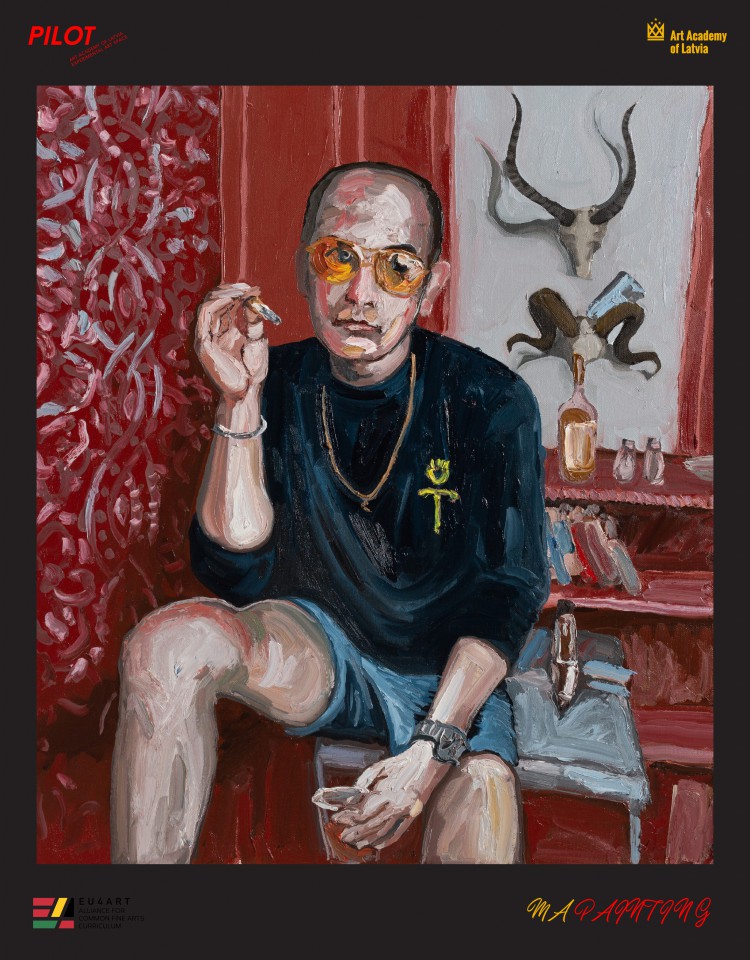

Having migrated to the Painting department from stage design, Kristīne Daukšte (1993) is quite naturally challenging genric traditions both in spatial and material terms. Together with professor and MA supervisor Amanda Ziemele, Daukšte uses her thesis to delve into human relations with space and the behavior, which manifests itself in conflict situations with others, with oneself and with gender and the space one must inhabit. Her works take the form of fictitious visual commentaries on the experience of conflict. Color, material, texture, the elements’ spatial relationships and the shifts in the meaning and use thereof upon encountering specific emotions all create a space where Daukšte would naturally place her works, should the current reality allow it. The artist is not worried that you can’t really tell if this work is a painting, a sculptural painting or an object. Even though the people at the department remind her, time and again, that it would perhaps be worthwhile to give color and brush a try, her free expression is not hindered.

Daukšte maintains that this approach is natural, seeing her past as a stage designer. ‘I am aware that I am not an artist that will work only on a canvas, using brush and color. I told everyone at the very start that my interests lie outside the canvas.’

Kristīne Kligina

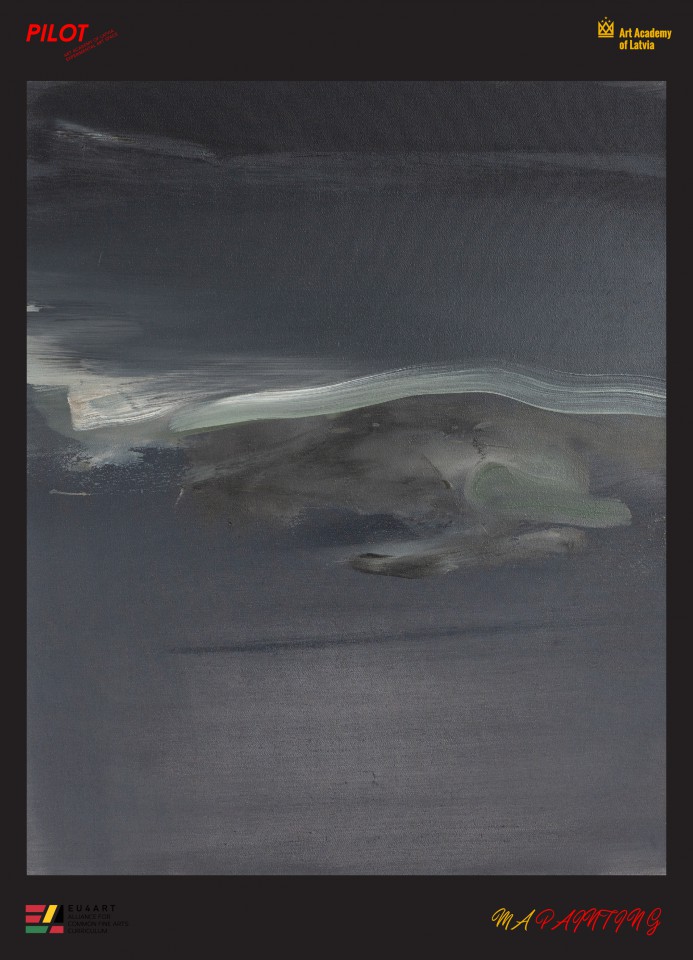

When painting her large-scale works, Kristīne Kligina (1973) usually puts them on the floor as it’s important for her to feel as if she’s located inside the work and experiencing its creation as a ritual, instead of making it as if from the side. Even though she saw painting as the next stage in her development, Kligina, educated and professionally engaged in textile arts, at first doubted whether she could live up to it and adjust. But she has found support at the department, and doubt has given place to satisfaction about her ability to fit inside the new environment. Even more, there have been times during her master’s studies when she was able to once again experience the feeling of buoyant excitement and discovery, usually witnessed only during undergraduate studies.

Kligina is working on her thesis with Ieva Iltnere, who challenged the artist to assume a minimalist approach, hitherto unfamiliar to her. At the same time, she is glad to have the chance to become influenced by such different teachers as Miķelis Fišers and Aleksejs Naumovs. In Kligina’s landscape paintings (when it was necessary to do so, she painted by the sea at a ten below cold), presence takes an important role alongside the incompleteness, allowing audiences and her own thought processes to fill in the gaps. This incompleteness and seeming opacity strive to reconnect to a mythological worldview, with its implicit ties to nature and their significance for modern humans assuming a special place in Kligina’s field of interest.

Liene Rumpe

Liene Rumpe’s (1996) sole work at the exhibition refers succinctly to several ever-present units in her quickly-shifting field of interest. This field houses points of intersection such as science, shamanism, mushrooms, matter and anti-matter, as well as the overproduction of being, art included. A new connection between these points has been established by the fear of death and salvation, or at least by a quest to find illusory safety in the era of a ‘new havoc’. Mushrooms could save us, but perhaps the kingdom of fungi is too chaotic. The nuclear mushroom, however, is definitely not our savior. Indeed, perhaps a mushroom is but an archetype. And at that, looking closely, you can see that a mushroom stalk resembles a human neck. The scientist and the shaman are often portrayed as antagonists, but both are trying to do good – particularly when it’s havoc all around.

Having studied the theoretical and practical fundamentals of canonical painting at the Janis Rozentāls Art School and the undergraduate program at the Art Academy of Latvia, Rumpe sees the graduate program as a way of questioning these fundamentals, stepping back from them and giving into experimentation. These attempts are aided both by professor Miķelis Fišers and his unconventional assignments (‘How would a work of art look on Mars?’), as well as her MA supervisor Amanda Ziemele’s openness and ideational interplay with the interests of Rumpe herself.

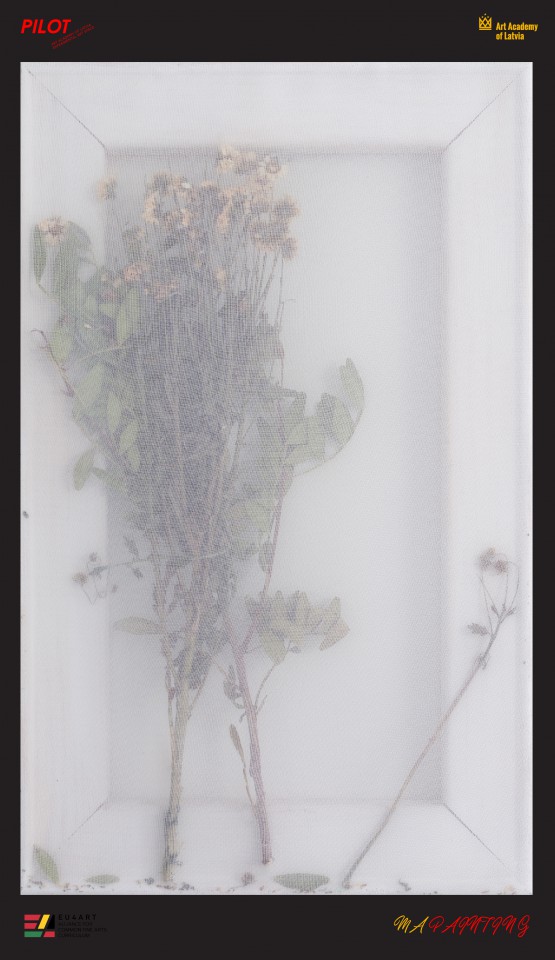

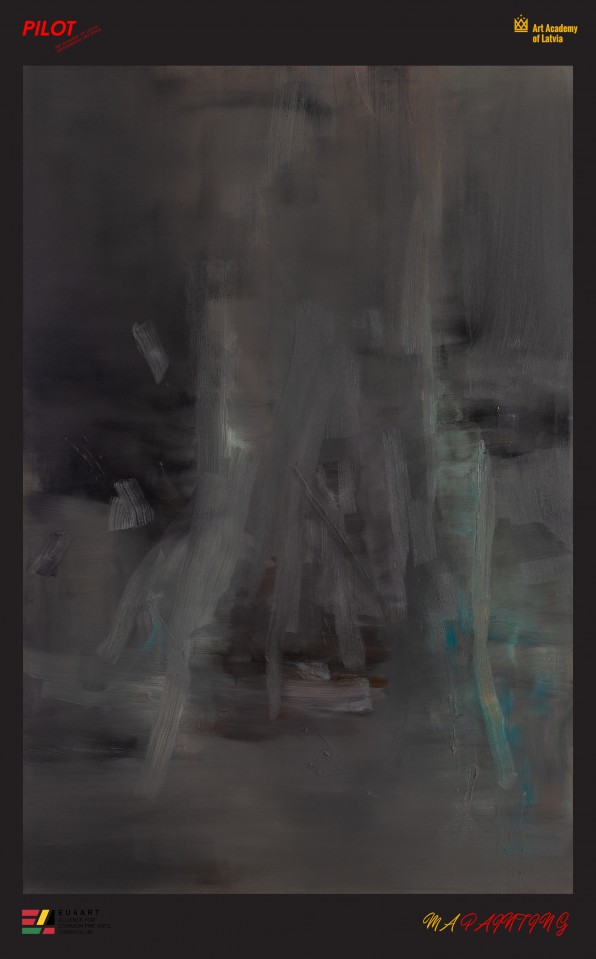

Madara Kvēpa

Madara Kvēpa’s (1996) show consists of works sparked by the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, when the majority of experts and the public turned their attention to people’s physical well-being, disregarding some aspects of mental health, which was affected directly by the inevitable security measures of the pandemic. Human well-being has several components, or at least two, namely physical and mental. The Latvian word for the desirable state of both – veselība (healthiness, related to vesels, ‘whole’) – has in its very meaning that a person is whole, complete, undivided.

Allowing the authorities and medical institutions to take care of her physical health, Kvēpa has assumed control over the second component of being healthy, experimenting with the different methods that ancient Latvian healing traditions offer, like burying herself fully in forest soil. (‘It felt as if after a sauna.’) Or crawling through an opening in a tree, which, in a ritual context, means crawling out of the mother’s womb again, a new beginning. Everything that Kvēpa does and subsequently translates into her work, she does on her own. Both because it’s fair and because she is interested in reconnecting directly with nature, an opportunity seemingly lost to modern humans.

With these four works, Kvēpa attempts to sort out the ‘tangle of personal thoughts’ brought about by the events of the previous year, as well as to partake in the department’s endless inside discussion on what painting is and what it means to every particular artist.

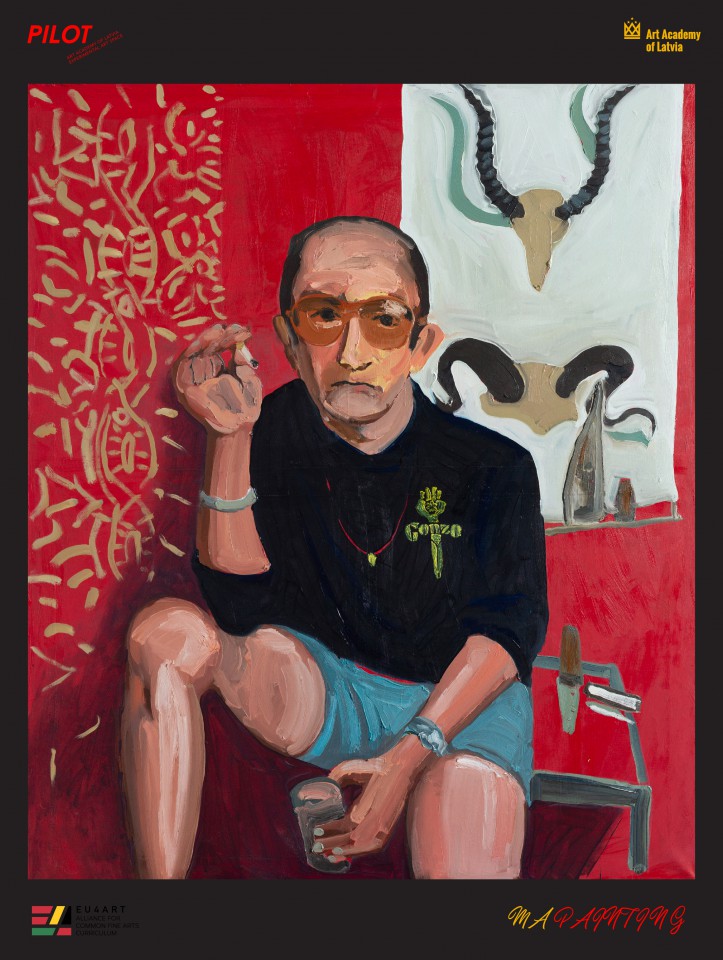

Atis Izands

Even though the obelisk of Atis Izands (1986) consists of attempts at self-identification motivated by his private history, the artist’s path towards the Painting department of the Art Academy of Latvia (LMA) has been rather natural, leading from the school’s drawing club to Roži, the Janis Rozentāls Art School, and to the undergraduate Painting department at LMA. Afterwards, Izands went on a considerable hiatus, during which he was able to organize a couple of solo shows. Upon returning to LMA eight years later, he noticed a ‘substantial [increase] in the use of English and openness to the world’.

Even though one routinely hears discussions on whether one must do actual painting at the Painting department, it doesn’t hinder Izands from doing personal research and striving to arrive at better formulations of this problem together with his MA supervisor Kristaps Ancāns.

The idea for the work on show can be tracked down at least to the 2019 solo exhibition Istabā sāk iemaldīties skudras (Ants Are Starting to Wander Into the Room). It has now materialized into an unnamed obelisk, covered with tiling, the design of which a specialist can trace chronologically.

As a male artist who has matured inside a typical post-Soviet environment, Izands is preoccupied with exploring social and sex roles in the context of a culturo-historical situation where the understanding of masculinity is still often tied to the typical image of a mužiks, a blue collar worker. Creating this obelisk proved to be hard work for Izands, allowing him to (finally?) lay claim to this aspect of masculinity as well. But he does not forget that even if one whitewashes and covers it with an IKEA parquet floor, the moldy Soviet tiles are still found at the bottom.

Reinis Bērziņš

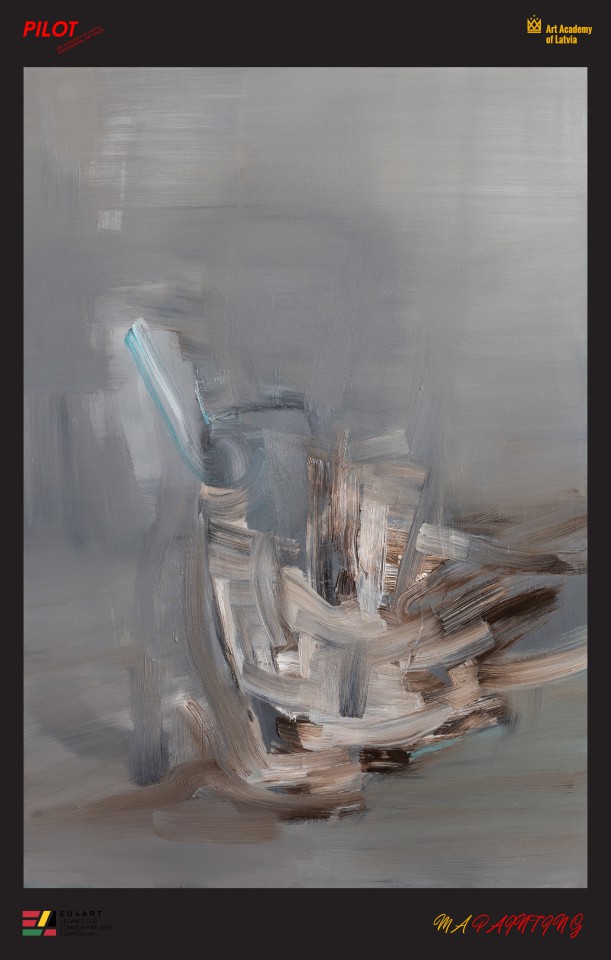

‘This is no sculpture department for you!’ Reinis Bērziņš (1989) would often hear this comment from professor Kristaps Zariņš. Did Bērziņš really do something the genre cannot allow to suffer, or did the professor toy with the fact that his student came to the Painting department after starting out as a sculptor? History will bury the answer. However, the comments did die down after a while, disappearing completely once Bērziņš finished his undergraduate studies in parallel and became distinguished enough to hold a couple of solo shows.

Three of Bērziņš’ works were picked for the exhibition, with abstract and figure painting seemingly tolerating each other’s presence (naturally, his MA supervisor is Ivars Heinrihsons). From time to time, landscape motifs spring up, making one ponder nature’s impersonality and cruelty almost in the manner of von Trier’s Antichrist.

But sound (prior to sculpture, Bērziņš’ principal occupation was music) and the third dimension are aspects the artist still wants to weave into his paintings, creating ever more intense relations between them – like in Valters Sīlis’ and Kate Krolle’s theater performance, Izskatās, ka tu mirsi (Looks Like You’re About to Die), for which Bērziņš created a kinetic sound installation.

Text: Helmuts Caune

Photo: Pēteris Vīksna